There seems to be an irresistible desire for boxing fans and pundits alike to contemplate which boxer of a given era was the best, pound for pound. I’ve always thought the whole issue was a dalliance into the absurd. Offsetting the natural attributes of each weight division in order to create some kind of parity between large and small is akin to calculating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Balancing the bone-numbing power of the Big Boys with the dazzling speed and resiliency of a mini mosca requires a refined set of definitions that are not easy to agree upon.

There seems to be an irresistible desire for boxing fans and pundits alike to contemplate which boxer of a given era was the best, pound for pound. I’ve always thought the whole issue was a dalliance into the absurd. Offsetting the natural attributes of each weight division in order to create some kind of parity between large and small is akin to calculating how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Balancing the bone-numbing power of the Big Boys with the dazzling speed and resiliency of a mini mosca requires a refined set of definitions that are not easy to agree upon. However, since physiology, athleticism, pugilistic skill, and ring achievement are subjective, I suppose I can no longer shirk my duty. So with a certain reluctance I join the throng, and make my case for the greatest fighter in my lifetime.

I will only consider fighters whose video record allows fair comparison. The grainy, jerky footage of boxers from the early part of the Twentieth Century, while fascinating, give few accurate clues to the skills of the fighters themselves. Fortunately, by the time of my birth, filmmaking had reached a respectable level, and archival footage of top-rated fighters remains available.

Rather than look for the biggest and baddest, and because medium-weight fighters exemplify the best attributes of all the divisions – mobility, speed, power, and the ability to take a punch – I will focus my insights on the 130 – 170 pound range. While fifteen to twenty pounds may be insignificant to a heavyweight, only a few extra pounds can catapult a smaller fighter into a different division, making a significant disparity in his level of competition.

I seek a fighter who personifies the essence of pugilism. A man who can’t wait to get into the ring, and whose character is defined by his ring presence and a desire to dominate everything inside it. A man undaunted by the noise of the crowd, hype, opposition, odds, or pundits. One who embodies the standard fare, and yet transcends it. One who, if he lived in ancient Greece, would not hesitate to strap on spiked gloves, or celebrate the Spartan philosophy of “come home with your shield, or on it.” A man who would mock jeering crowds of the Roman Coliseum. A fighter who has proved his skill in the ring over multiple eras and weight divisions, showing flexibility and an ability to change strategies to prevail over larger, stronger opponents, and the passing of time.

Being undefeated is not an important consideration. Some boxers snarl like a lion before entering the ring only to mew like a kitten after defeat. A loss can improve a great fighter, leaving the taste of metal in his mouth, and a desire for revenge.

Last, but not least, I want a fighter imbued with true bloodlust, the killer instinct, the acute confidence of a predator blended with an overwhelming desire to take down prey. A fighter who senses when his opponent is ready to fall, and never hesitates to go in for the kill. A fighter who proudly carries that fierce part of our hunter ancestor’s DNA that remains intact, brought alive inside the ring.

And the winner is …

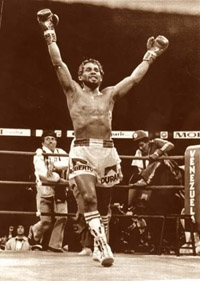

There is no fighter in my lifetime who fits these criteria more than a man called, Manos De Piedra, the magnificent fighting machine known as Roberto Duran.

There is no fighter in my lifetime who fits these criteria more than a man called, Manos De Piedra, the magnificent fighting machine known as Roberto Duran. When it comes to the chiaroscuro of boxing, nobody epitomizes it like Duran. His brooding, almost psychopathic stare made Sonny Liston’s seem like a warm smile from Mother Teresa. And he never took those eyes off his opponent whether ducking, dodging, or being tagged. He fixed the other guy in his sights and never waivered.

Duran’s dominance in four weight divisions, over thirty-three years and 119 fights, is nearly unparalleled. His nickname, “Hands of Stone,” only told half the story. “Chin of Stone” would have been just as appropriate. Few boxers had a better set of whiskers, or could roll with punches like Duran.

Duran was a pure boxer-puncher, but punching was his “raison d’etre.” He innately understood leverage and forward momentum, achieving perfect extension on his punches, especially the right hand. This forward energy often propelled him over his prostrate victims, characterized by a hopping skip he instinctively used to avoid stepping on his opponents as they lay prone on the mat.

Duran would anxiously pound his gloves together in his corner before a fight, waiting for the bell, all the while staring at his opponent across the ring like a starved beast anticipating a succulent meal. Using looping punches to the body, and small steps to the side, he was masterful at cutting off the ring. Part bull, part matador, he could maul or parry, and the concept of retreat had no place in his lexicon.

You always knew a Duran fight would be exciting. Except for his “no mas” bout against Sugar Ray Leonard, Duran was determined to win or go down for the count, which he did only once - when Thomas Hearns hit him flush on the chin with a cobra-like right after feinting to Duran’s midsection in their 1984 WBC Light Middleweight fight. Even in his 1998 TKO loss to William Joppy, at age forty-seven and grossly out of shape, Duran was a formidable opponent until referee Joe Cortez stopped the fight in the 3rd round. His only other TKO loss occurred when he could no longer continue because an injury during his fight with journeyman Pat Lawlor.

You always knew a Duran fight would be exciting. Except for his “no mas” bout against Sugar Ray Leonard, Duran was determined to win or go down for the count, which he did only once - when Thomas Hearns hit him flush on the chin with a cobra-like right after feinting to Duran’s midsection in their 1984 WBC Light Middleweight fight. Even in his 1998 TKO loss to William Joppy, at age forty-seven and grossly out of shape, Duran was a formidable opponent until referee Joe Cortez stopped the fight in the 3rd round. His only other TKO loss occurred when he could no longer continue because an injury during his fight with journeyman Pat Lawlor.

Duran was magnificent defensive fighter. Not only did he practice the axiom that the best defense is a good offense, but he had an uncanny way of anticipating a punch. As one landed he would turn his head with the punch, thereby neutralizing much of its power.

Duran was magnificent defensive fighter. Not only did he practice the axiom that the best defense is a good offense, but he had an uncanny way of anticipating a punch. As one landed he would turn his head with the punch, thereby neutralizing much of its power. He had a skill that only the elite of boxing exhibit. Even with bigger men, he had the confidence to stand his ground, deflect punches with his shoulders and arms, and stay in position to return fire. This was even more evident as he moved up in weight. In his extraordinary wins over, Pipino Cuevas, Davey Moore and Iran Barkley – all larger men – Duran walked into the eye of the storm, made his opponents miss, countered, and dropped all of them. Even against formidable middleweight punchers like Marvin Hagler, and Robbie Sims, Duran rarely took a backward step.

He struggled with weight the last part of his career, rarely training between fights. A few months before his title match with Barkley, it was rumored that he was close to 190 pounds before training camp, but emerged victorious in one of the most thrilling fights of his long career. Duran’s defiant stance, win or lose, was a hallmark of his defiant machismo.

Duran’s Career Highlights

Roberto Duran made his pro debut in 1968 at 119 pounds. By 1972 he owned the WBA Lightweight title after a controversial TKO of Ken Buchanan. Later that same year he lost a ten-round non-title fight to Esteban De Jesus. But he learned from his loss and went on to rule the division with a Reign of Terror for nearly six years, including two retribution KO’s of De Jesus.

Roberto Duran made his pro debut in 1968 at 119 pounds. By 1972 he owned the WBA Lightweight title after a controversial TKO of Ken Buchanan. Later that same year he lost a ten-round non-title fight to Esteban De Jesus. But he learned from his loss and went on to rule the division with a Reign of Terror for nearly six years, including two retribution KO’s of De Jesus.

In September of 1978 he moved up in weight after defeating De Jesus for the second time over three fights. Though he was still knocking out opponents at this new weight, four ten-round decisions left his fans wondering if he’d left most of his punching power at lightweight.

Roberto Duran made his pro debut in 1968 at 119 pounds. By 1972 he owned the WBA Lightweight title after a controversial TKO of Ken Buchanan. Later that same year he lost a ten-round non-title fight to Esteban De Jesus. But he learned from his loss and went on to rule the division with a Reign of Terror for nearly six years, including two retribution KO’s of De Jesus.

Roberto Duran made his pro debut in 1968 at 119 pounds. By 1972 he owned the WBA Lightweight title after a controversial TKO of Ken Buchanan. Later that same year he lost a ten-round non-title fight to Esteban De Jesus. But he learned from his loss and went on to rule the division with a Reign of Terror for nearly six years, including two retribution KO’s of De Jesus. In September of 1978 he moved up in weight after defeating De Jesus for the second time over three fights. Though he was still knocking out opponents at this new weight, four ten-round decisions left his fans wondering if he’d left most of his punching power at lightweight.

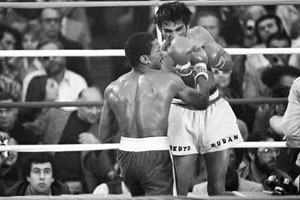

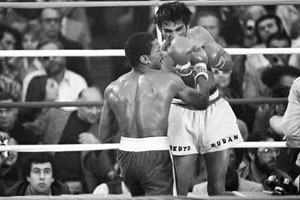

This changed after his meeting with former WBC Welterweight champion Carlos Palomino, whom he dominated and knocked down in the 6th round. Then, in his welterweight championship fight with Sugar Ray Leonard the next year, Duran had the young champion rubber-legged several times in the first three rounds on the way to a fifteen-round unanimous decision.

This changed after his meeting with former WBC Welterweight champion Carlos Palomino, whom he dominated and knocked down in the 6th round. Then, in his welterweight championship fight with Sugar Ray Leonard the next year, Duran had the young champion rubber-legged several times in the first three rounds on the way to a fifteen-round unanimous decision.

After a failed bid to take Wilfredo Benitez’s WBC Light Middleweight crown, Duran again proved his mettle in a sizzling fight with Mexican slugger Pipino Cuevas. Both former welterweight champions landed frequently in their 1983 collision until Duran’s chin prevailed in the fourth round. This win set up a match with the talented but inexperienced WBA Light Middleweight Champion, Davey Moore. Winning the title after only twelve professional fights, Moore was no match for the experience and determination of Duran, and he took a beating on the way to an eighth round stoppage on Duran’s 32nd birthday.

After a failed bid to take Wilfredo Benitez’s WBC Light Middleweight crown, Duran again proved his mettle in a sizzling fight with Mexican slugger Pipino Cuevas. Both former welterweight champions landed frequently in their 1983 collision until Duran’s chin prevailed in the fourth round. This win set up a match with the talented but inexperienced WBA Light Middleweight Champion, Davey Moore. Winning the title after only twelve professional fights, Moore was no match for the experience and determination of Duran, and he took a beating on the way to an eighth round stoppage on Duran’s 32nd birthday. Only five months later, having won championships in three different weight divisions, Duran decided to go for broke and challenged Marvelous Marvin Hagler for the undisputed Middleweight Championship of the world. In a squeaker, Hagler barely managed to outpoint Duran’s onslaught.

If he couldn’t have the middleweight title, Duran decided to consolidate the light middleweight titles. But because he neglected to fight number one contender, Mike McCallum, he was stripped of his WBA crown.

The fight for Thomas Hearns’ WBC Light Middleweight title was a night few boxing fans will forget. Almost an exact replay of Hearns’ welterweight blowout of Pipino Cuevas, Duran was never a factor in the fight. Hearns’ size, reach and power were insurmountable as he used them to drop Duran three times in two rounds, the last putting Duran on his face in a semi-comatose state. For most ringside observers, it appeared to be the end of Duran, and the beginning of a new era.

The fight for Thomas Hearns’ WBC Light Middleweight title was a night few boxing fans will forget. Almost an exact replay of Hearns’ welterweight blowout of Pipino Cuevas, Duran was never a factor in the fight. Hearns’ size, reach and power were insurmountable as he used them to drop Duran three times in two rounds, the last putting Duran on his face in a semi-comatose state. For most ringside observers, it appeared to be the end of Duran, and the beginning of a new era. But Duran had other plans, emphasizing what makes Duran the greatest fighter in my time. He took a year and a half off, and got back in the saddle with two KO wins in his home of Panama City. Two years after his devastating loss to Hearns he dropped a ten-round split decision to veteran Robbie Sims in Las Vegas. But this loss did not dissuade him.

Six wins and three years later, Duran challenged the new WBC Light Middleweight Champion, Iran Barkley, after Barkely flattened Hearns with an unexpected right hand in their 1988 bout. Not given much of a chance against the younger and stronger champion, Duran silenced all the naysayers when he pummeled Barkley and dropped him in the eleventh round on his way to a twelve-round split decision. The legend had returned.

It was a short-lived revival. By the end of the year he had lost the title in a lopsided decision to Ray Leonard in their third meeting, and had to throw in the towel after six rounds with Pat Lawlor because of a shoulder injury.

Although he went on to fight twenty-five more times, his light was dimmer, and each fight was an uphill struggle. Between 1994 and 2001, he lost to Jorge Fernando Castro, Omar Eduardo Gonzalez, twice each to Hector Camacho and Vinny Pazienza, and a TKO loss to William Joppy – men whom he would have crushed in his prime.

Manos de Piedra fights on in our memories, and in the vast legacy he left behind. To me, he still stands head and shoulders above all others, and represents the standard by which all boxers must be judged.

----------end-------------

Charles Long

www.convictedartist.com

| Comments |

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||