"It is no superficial thing, a fad of a moment or a generation. It is as deep as our consciousness, and is woven into the fibers of our being. This is the ape and tiger in us, granted, but it is in us, isn't it? "

"It is no superficial thing, a fad of a moment or a generation. It is as deep as our consciousness, and is woven into the fibers of our being. This is the ape and tiger in us, granted, but it is in us, isn't it? "

-Jack London

"(Boxing is) the one great physical sport in which actual personal superiority can ever be authoritatively tested."

- Boxing Magazine (in anticipation of the Jack Johnson/Jim Jeffries fight of 1910)

A few weeks ago I was at a luncheon with friends and acquaintances in a upscale suburb of Phoenix. While nibbling pasta primavera and chatting about sports, I dropped an innocuous comment about my affection for boxing. A quiet pall descended over the conversation and the woman across from me contorted her face as though she’d smelled something foul. “I don’t see how can anybody enjoy a sport where the goal is for two people to beat each other senseless,” she said dismissively. I knew her slightly, so even before she opened her mouth, I was prepared for the onslaught.

In the split second between inhaling and commencing my reply, our host deftly changed the subject, sideswiping my response. What was the point of an argument anyway? It was doomed to be a stalemate of ideas against emotions, so I bit my lip in the spirit of congeniality. But I couldn’t quash the cacophony ricocheting across my brain.

In the split second between inhaling and commencing my reply, our host deftly changed the subject, sideswiping my response. What was the point of an argument anyway? It was doomed to be a stalemate of ideas against emotions, so I bit my lip in the spirit of congeniality. But I couldn’t quash the cacophony ricocheting across my brain.

Baseball was well established by the turn of the Twentieth Century, but by the days of Jack Johnson and Seabiscuit, boxing was arguably second in popularity only to horse racing. Widespread attempts to ban both sports during a surge in progressive movements were only marginally successful.

I remember my grandmother’s anecdotes of bloody matches during the 20's and 30's when my grandfather reviewed boxing for his newspaper column. Weekly fights were commonplace and crowds packed arenas all over America. But all the while, boxing was under attack.

Boxing was, and is, reviled by many. Dr. George Lundberg, one time editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, labeled boxing an "obscenity" that "should not be sanctioned by any civilized society.” Because of this belief, and due to its own internal problems, boxing has often been relegated to a fringe fan base that has barely sustained it. Nonetheless, boxing continues to survive in one form or another.

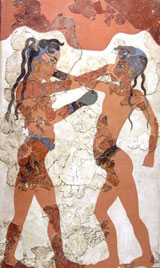

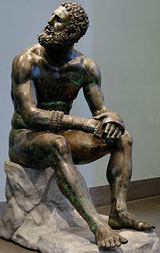

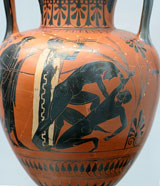

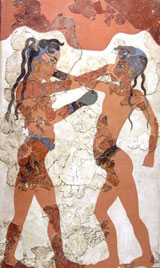

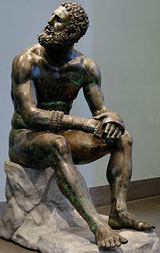

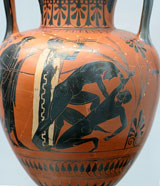

I began to wonder what event in the cultural landscape, starting around 1900, shifted perceptions about the favorability of unarmed combat? What spawned a worldwide movement seeking to end a sport that was lauded even before the Greeks tied strips of animal hide over their knuckles at the 20th Olympiad in 688 BC?

I began to wonder what event in the cultural landscape, starting around 1900, shifted perceptions about the favorability of unarmed combat? What spawned a worldwide movement seeking to end a sport that was lauded even before the Greeks tied strips of animal hide over their knuckles at the 20th Olympiad in 688 BC?

At the risk of sounding misogynistic, I could initiate a sociological rant about the feminization of modern culture, and how it has distorted the primordial instincts that brought our ancestors from the plains of Africa to Mare Tranquillitatis on the lunar surface.

But it is probably more appropriate to mount an anthropological defense - one aimed at Homo sapiens' compulsion to risk great peril to achieve some small speck of greatness, an instinct that comes, not out of a desire to better mankind, but a desire for personal glory, an impulse to compete, defeat and prevail.

Even within the disciplines of business, art, science and medicine, it is the warrior spirit of competition, not altruism, that spawns the catalyst for the preponderance of man's achievements. And some of the last pure remnants of that indomitable spirit remain manifest in a sport that pits one man against another in a pugilistic struggle for dominance. It is virtuosity on the most fundamental plane – a stylized dance depicting a ritual in the battle for survival. Yes, it is brutal. And it is good.

Even within the disciplines of business, art, science and medicine, it is the warrior spirit of competition, not altruism, that spawns the catalyst for the preponderance of man's achievements. And some of the last pure remnants of that indomitable spirit remain manifest in a sport that pits one man against another in a pugilistic struggle for dominance. It is virtuosity on the most fundamental plane – a stylized dance depicting a ritual in the battle for survival. Yes, it is brutal. And it is good.

Unlike cockfighting, dog-fighting, or tauromachy, the men who enter the square ring are not placed there against their will. Pugilists are decisive in their desire to risk life, health, and ego in their dedication to engage in the pas de deux of fisticuffs that dates back to antiquity.

If one views boxing as a ballet of athleticism at its most ferocious, without diminishing its value  because of the bellicose nature of sport, there is much to appreciate. While knocking your opponent unconscious is always an option, it’s more about hitting without being hit, using reflexes, footwork, and conditioning to carry out a detailed strategy as you analyze the subtleties of your opponent's body language. Few other athletes have the level of stamina required to sustain constant motion for a dozen three-minute rounds. And around the turn of the last century, matches of 30-40 rounds were not uncommon. With the longest recorded fight ending in a draw after 110 rounds, boxing is not the turf of the timid or the undisciplined.

because of the bellicose nature of sport, there is much to appreciate. While knocking your opponent unconscious is always an option, it’s more about hitting without being hit, using reflexes, footwork, and conditioning to carry out a detailed strategy as you analyze the subtleties of your opponent's body language. Few other athletes have the level of stamina required to sustain constant motion for a dozen three-minute rounds. And around the turn of the last century, matches of 30-40 rounds were not uncommon. With the longest recorded fight ending in a draw after 110 rounds, boxing is not the turf of the timid or the undisciplined.

The repugnance toward boxing seems to be hinged on the fact that punches are "intended" to hurt or stun the opponent, rather than tallying the rate of permanent damage the sport might inflict. There are other sports with far greater numbers of debilitating injuries which seem to stir little ire. What about football? What about hang gliding, which has some of the highest fatality rates? Should that be banned too? Automobiles are some of the greatest killers of human beings; why not ban them as well?

Instead, taking a page from the Gun Control and Hate Crimes play-books, opponents of boxing refer to the "intent" of the sport rather the body count. I notice that it is generally those who support a statist society - one where the oversight of government authority supersedes an individual's right to govern himself - who are most ready to support such bans.

I have a very dear friend who is my polar opposite in terms of political and philosophical views. When we were young we watched boxing together on a regular basis. But after he made a major political shift, I was stunned to hear him say, "Boxing should probably be banned, and I'm ashamed to say I still enjoy it."

His rationale was that injured boxers represent a substantial cost to society in health care expenses due to brain injury. I question that it is a "substantial cost to society," and I suspect his motivation goes much deeper than that. I believe it comes from an intellectual elitism that perceives most boxers as lower class, and unsophisticated to the point of being unable to effectively make decisions for themselves. Therefore, society has an obligation to intervene on their behalf.

cost to society," and I suspect his motivation goes much deeper than that. I believe it comes from an intellectual elitism that perceives most boxers as lower class, and unsophisticated to the point of being unable to effectively make decisions for themselves. Therefore, society has an obligation to intervene on their behalf.

This mindset burgeoned in the 1890's with the beginning of the women's suffrage movement, along with other progressive causes. Followers believed that government was a viable tool for social change, and quickly targeted alcohol, guns, gambling, prostitution and boxing. The Industrial Revolution resulted in a prosperity that gave do-gooders more free time to become involved in other people's private affairs, and goals they believed would create a "greater good."

Some of these movements had noble intentions, such as racial and gender equality. Others were misguided attempts to redefine Mankind, stripping it of its aggressive, immoral, and inconvenient tendencies. But even the most well-intentioned causes have unintended consequences.

There are paradigms that embrace all man’s endeavors when broken down to their lowest common denominator - the primal urges that define life as we know it. And where are these qualities better exemplified than in art, science and extreme sports? When viewed without moral judgment they all have a cogent bond. Denying all that is fierce in human nature is not only a denial of who we are, but a rejection of that which accounts for our success as a species.

Boxing replays the timeless drama of man versus nature, by pitting one man against another. There are few moments more definitive than a boxer sitting atop the shoulders of an adoring crowd, his arms raised in victory after overcoming his opponent with only his hands as weapons. It is an intricate amalgam of beauty and savagery.

Boxing replays the timeless drama of man versus nature, by pitting one man against another. There are few moments more definitive than a boxer sitting atop the shoulders of an adoring crowd, his arms raised in victory after overcoming his opponent with only his hands as weapons. It is an intricate amalgam of beauty and savagery.

Granted, there are tragedies in the ring. But life is fraught with danger for those who choose to live on the edge. I was in the Olympic Auditorium the night Kiko Bejines received injuries that took his life three days later. Mohammed Ali is a shadow of his former self, trauma-induced Parkinson’s having silenced him long before his time. Poised on the edge of greatness, middleweight champion Gerald McClellan was left with no vision and little hearing after his epic battle with Nigel Benn. But had they not taken the risks and gone on to live unremarkable lives, we would know nothing of them or their deeds.

As portrait artist Richard T. Slone wrote in his testament to Gerald McClellan and his fallen comrades: "It's better to live just one day as a lion, than a lifetime as a lamb."

Charles Long

www.convictedartist.com

"It is no superficial thing, a fad of a moment or a generation. It is as deep as our consciousness, and is woven into the fibers of our being. This is the ape and tiger in us, granted, but it is in us, isn't it? "

"It is no superficial thing, a fad of a moment or a generation. It is as deep as our consciousness, and is woven into the fibers of our being. This is the ape and tiger in us, granted, but it is in us, isn't it? " In the split second between inhaling and commencing my reply, our host deftly changed the subject, sideswiping my response. What was the point of an argument anyway? It was doomed to be a stalemate of ideas against emotions, so I bit my lip in the spirit of congeniality. But I couldn’t quash the cacophony ricocheting across my brain.

In the split second between inhaling and commencing my reply, our host deftly changed the subject, sideswiping my response. What was the point of an argument anyway? It was doomed to be a stalemate of ideas against emotions, so I bit my lip in the spirit of congeniality. But I couldn’t quash the cacophony ricocheting across my brain.  I began to wonder what event in the cultural landscape, starting around 1900, shifted perceptions about the favorability of unarmed combat? What spawned a worldwide movement seeking to end a sport that was lauded even before the Greeks tied strips of animal hide over their knuckles at the 20th Olympiad in 688 BC?

I began to wonder what event in the cultural landscape, starting around 1900, shifted perceptions about the favorability of unarmed combat? What spawned a worldwide movement seeking to end a sport that was lauded even before the Greeks tied strips of animal hide over their knuckles at the 20th Olympiad in 688 BC?  Even within the disciplines of business, art, science and medicine, it is the warrior spirit of competition, not altruism, that spawns the catalyst for the preponderance of man's achievements. And some of the last pure remnants of that indomitable spirit remain manifest in a sport that pits one man against another in a pugilistic struggle for dominance. It is virtuosity on the most fundamental plane – a stylized dance depicting a ritual in the battle for survival. Yes, it is brutal. And it is good.

Even within the disciplines of business, art, science and medicine, it is the warrior spirit of competition, not altruism, that spawns the catalyst for the preponderance of man's achievements. And some of the last pure remnants of that indomitable spirit remain manifest in a sport that pits one man against another in a pugilistic struggle for dominance. It is virtuosity on the most fundamental plane – a stylized dance depicting a ritual in the battle for survival. Yes, it is brutal. And it is good. because of the bellicose nature of sport, there is much to appreciate. While knocking your opponent unconscious is always an option, it’s more about hitting without being hit, using reflexes, footwork, and conditioning to carry out a detailed strategy as you analyze the subtleties of your opponent's body language. Few other athletes have the level of stamina required to sustain constant motion for a dozen three-minute rounds. And around the turn of the last century, matches of 30-40 rounds were not uncommon. With the longest recorded fight ending in a draw after 110 rounds, boxing is not the turf of the timid or the undisciplined.

because of the bellicose nature of sport, there is much to appreciate. While knocking your opponent unconscious is always an option, it’s more about hitting without being hit, using reflexes, footwork, and conditioning to carry out a detailed strategy as you analyze the subtleties of your opponent's body language. Few other athletes have the level of stamina required to sustain constant motion for a dozen three-minute rounds. And around the turn of the last century, matches of 30-40 rounds were not uncommon. With the longest recorded fight ending in a draw after 110 rounds, boxing is not the turf of the timid or the undisciplined.  cost to society," and I suspect his motivation goes much deeper than that. I believe it comes from an intellectual elitism that perceives most boxers as lower class, and unsophisticated to the point of being unable to effectively make decisions for themselves. Therefore, society has an obligation to intervene on their behalf.

cost to society," and I suspect his motivation goes much deeper than that. I believe it comes from an intellectual elitism that perceives most boxers as lower class, and unsophisticated to the point of being unable to effectively make decisions for themselves. Therefore, society has an obligation to intervene on their behalf.  Boxing replays the timeless drama of man versus nature, by pitting one man against another. There are few moments more definitive than a boxer sitting atop the shoulders of an adoring crowd, his arms raised in victory after overcoming his opponent with only his hands as weapons. It is an intricate amalgam of beauty and savagery.

Boxing replays the timeless drama of man versus nature, by pitting one man against another. There are few moments more definitive than a boxer sitting atop the shoulders of an adoring crowd, his arms raised in victory after overcoming his opponent with only his hands as weapons. It is an intricate amalgam of beauty and savagery.